|

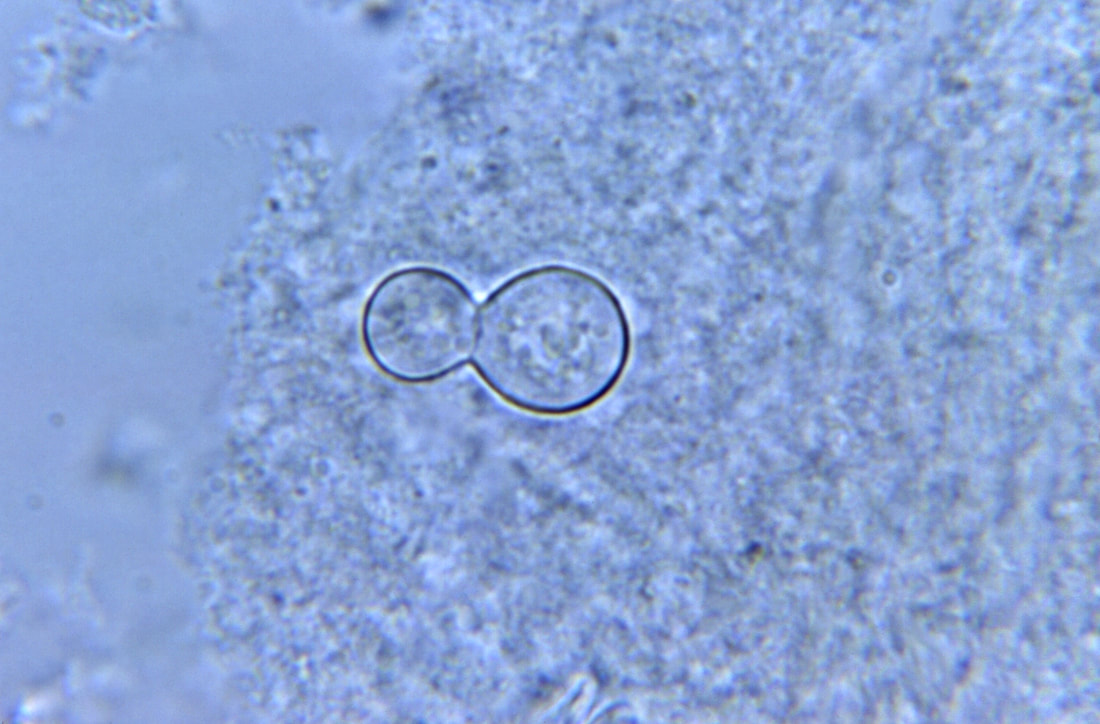

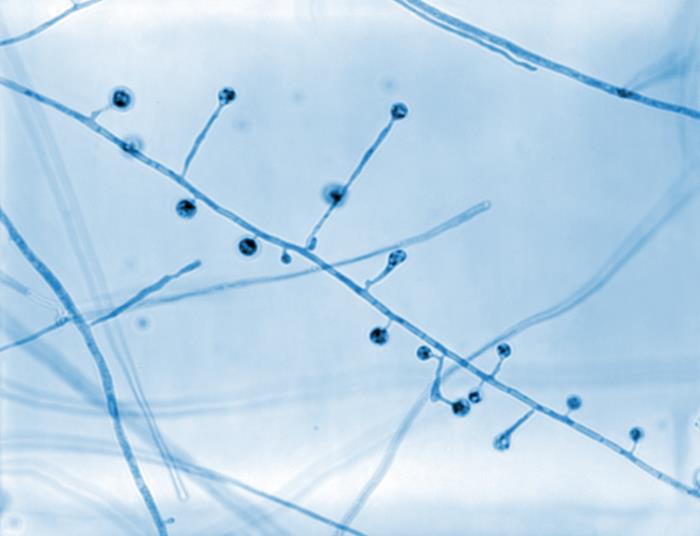

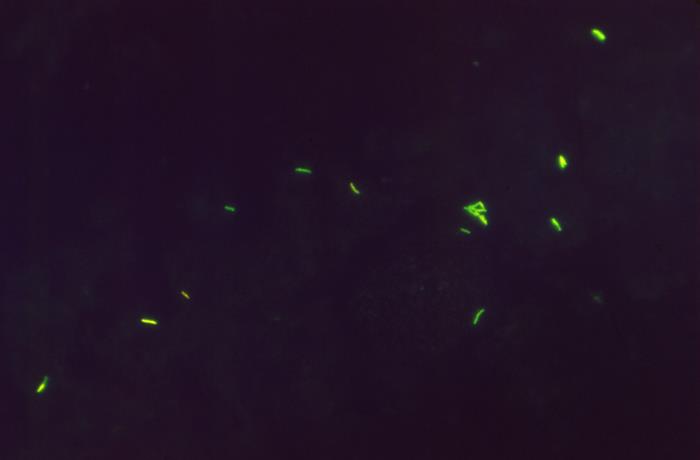

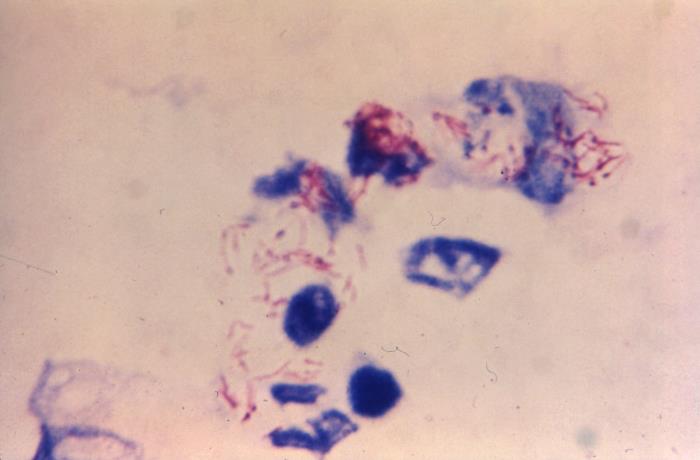

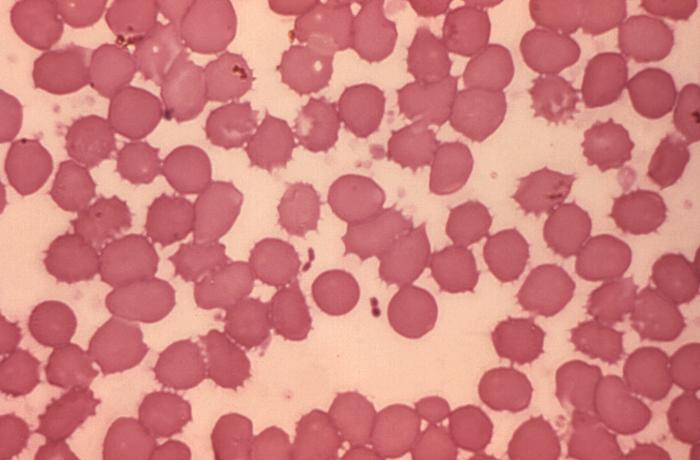

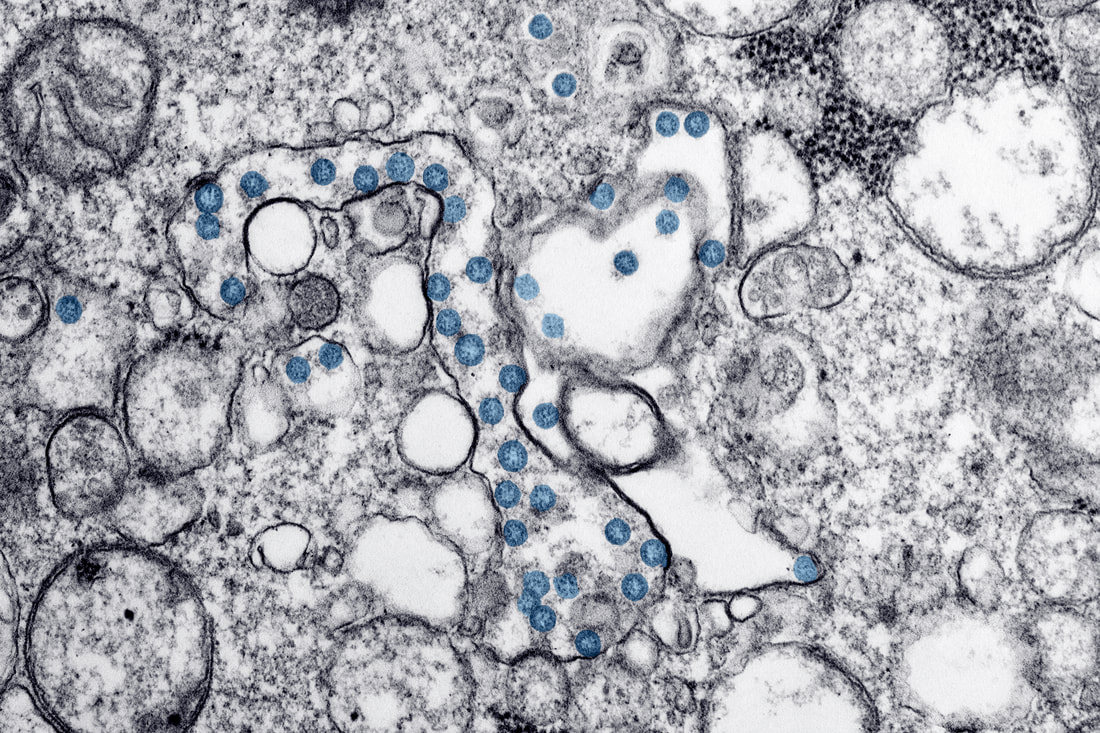

I have always been fascinated by the world of small. Even now--especially now, with the pandemic turning our world into a frightening, unfamiliar place--going into the woods behind our house to see how spring is unfolding along the creek is a chance for much needed peaceful meditation. Here I rediscover my childhood wonder in the quiet variety of life around me and become lost in observing. And while it's exciting to catch a glimpse of the larger fauna, a deer, or, like last summer, a Great Blue Heron startled into flight just a few feet away from me, it is the quiet, still, and very small that fascinates me most. I've been rereading Emily Carr's The Book of Small, a collection of stories and vignettes from Carr's childhood she wrote much later in life. As a child, I had read all of Carr's books that I could get my hands on from the local library. She was one of my heroes. I shared her love of nature and enjoyed her keen observation of adult life. That she became one of Canada's most renowned painters just proved to me that it was ok to be a weird little kid who liked to spend a lot of time in the bush by herself. In her introduction to The Book of Small, Sarah Ellis writes: Carr's description of this same perception, the feeling of an almost achievable state of synaesthetic integration and joy in which one will see into the living heart of things, has a feeling of immediacy, detail and authenticity. To be able to see into the living heart of things... Last fall was a great time for mushrooms, plenty of rain and a late frost. Here is a still life that would fit on a dime. A bit of moss (Knight's Plume?) and a tiny mushroom (probably a Mycena species) at the base of a larger mushroom. A piece of black crust fungus (probably Ustulina sp.) from a dead alder branch. I didn't see the snail till I had the sample in my house and was looking at it through my macro lens. The little piece of green lichen is about 2 to 3 mm wide. Below are pictures of a fungus I had never seen in its macroscopic form before, though I have seen many rotting pieces of wood lying on the ground and stained a strange blue-green and wondered what that was all about. These are the fruiting bodies of Chlorociboria aeruginascens, commonly known as Green stain fungus. The blue-green stain is a result of the microscopic hyphae invading the wood and releasing a pigment called xylindein. These lovely little fruiting bodies, often called Elf Cups (though they look more like Elf Ears to me) are only about 1 cm wide at most. The hyphae (the microscopic fungal filaments that are hiding in the rotting wood underneath) are maybe 2 to 3 micrometers wide. One centimetre is one one-hundredth of a metre. One micrometer is one one-millionth of a meter. Bear with me as I go on about these measurements, because I would like to take you into a world I spent my working life in, one in which some of the "invisible" beings we worked with could kill you or at least make you very sick. And, believe it or not, even in this world, as I searched in Petri dishes and under microscopes for creatures most people would think of as their enemies, I would often experience that feeling of synaesthetic integration and joy in which one will see into the living heart of things. I was not alone. Whenever anyone in the lab found something interesting under the microscope, they'd call their colleagues over for a look. Of course there was the feeling of having done your job well, having helped find a diagnosis for the patient, but that feeling was often infused as well with this particular sense of wonder. I imagine these moments are repeated in microbiology labs the world over. These innocuous looking bubbles are the yeast form of Blastomyces dermatitidis as seen in a sample of sputum. There are at least 120,000 known species of fungi in the world, and probably many times that number of unidentified fungal species. Only a small number of fungi are pathogenic to humans. "Blasto", as we called it in the lab, is one of them. It's a dimorphic fungus--meaning it has a yeast form at body temperature, and a filamentous form in the environment. It can cause a severe pulmonary infection, or skin lesions, or invade the the central nervous system of an immunocompromised host. Dogs, with their need to experience so much of the world through their noses are particularly vulnerable to Blasto, which grows in the soil and decaying matter. The yeast cells above are about 8 to 10 micrometers wide. Below is a picture of the filamentous form that could be found in the environment, if you could distinguish it from all the other thousands of fungal filaments in the soil. This sample is growing on a Petri dish and is what we would see in the lab. These filaments are about 1 to 3 micrometers wide, similar to the Blue stain fungus above. The round spores, or conidia, are thought to be the infectious part of the fungus. When they are small, about 4 micrometers, they can be inhaled deeply into the lung. Back when our lab was still doing TB culture, we spent a lot of time sitting in a darkened room looking through a microscope equipped with an ultraviolet light source. I often felt like I was travelling through dark space looking for signs of alien life. The smears made from the patients' sputum samples were stained with a special dye that caused the tuberculosis bacilli to fluoresce under the UV light. This made it much easier for us to spot the bacilli in a messy sample. These little green rods below are Mycobacteria tuberculosis, about 2 to 4 micrometers in length and 0.2 to 0.5 micrometers wide. You could fit these in sideways in the fungal hyphae shown above, sort of like matchsticks in a box. Below is a sample stained with Ziehl-Neelson stain. The purple blobs are puss cells and the stringy pink filaments are the tuberculosis bacilli. In a messy sample it would be hard to differentiate these red forms from other background material. The fluorescent stain helps make the microscopic screening of patient samples much more efficient. Now, more and more sensitive techniques such as PCR are being used to detect many of these diseases. Below is a beastie I never got to meet in real life, thank God. This is a blood smear from a patient with septicemic Plague. The large pink cells are rather stressed red blood cells. The plague bacilli (Yersinia pestis) are the darker red dots in between the blood cells in the middle of the picture and some are sitting on top of the red cells here and there. They're about 1 to 3 micrometers long and 0.5 to 0.8 micrometers wide. In the same size ballpark as the TB bacilli. Below we have the current plague agent. Covid-19, the little blue guys, are about 120 nanometers wide, or 0.12 micrometers. About 4 or 5 of these would fit across the width of a plague bacteria.

This image was taken with an electron microscope (EM). An EM is a large instrument that uses a series of electromagnets to focus a beam of electrons onto the sample. We used to have a cranky one of these in the lab. It looked like a stainless steel bomb perched on its end on a small table, with a set of eye pieces on the side of the bomb and a small glass chamber at its base. At the base of the glass chamber was a flat surface that showed a phosphorescent image of the sample, which had been inserted on a special needlelike holder throw a small aperture half way up the bomb's body. The room was also darkened while the tech worked. It always reminded me of scenes in submarines where someone is watching the glowing sonar screen for signs of enemy vessels. The EM required a vacuum pump to clear the chamber of air and a water pump to keep the system cool and a silly amount of maintenance. You could tell when someone had fired it up because the rumble could be felt in the floors of the adjacent rooms. Now, there are better, faster and more sensitive ways of detecting viruses and EMs are mostly used for research, not for regular diagnostic work. The world of small is just as real as the world of big, or the world of manmade, but so many of us are caught up in the world of big and manmade, the world of small becomes unreal and not worth paying attention to. We become like the dwellers of Flatland in Edwin A. Abbott's 1884 novel, so used to their two-dimensional world and its hierarchies and dramas they cannot imagine the possibility of any other dimension. And like the rulers in Flatland, many of our leaders were in denial--at first-- that this creature from another dimension, this Covid-19, could have any effect on our world and society. They didn't believe the epidemiologists and microbiologists, those who could see into the world of small and warn us of what was coming.

4 Comments

|

AuthorI'm Elizabeth Pszczolko, a writer living in the woods outside Thunder Bay, Ontario. As a child, I used to keep scrapbooks of nature stuff - drawings, musings, poems. This is my grown up (I use the term loosely) version of those long lost works. For more on what inspires this blog, please see the About page. Archives

November 2023

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed